THE MEDICAL REPORT Part 1 of 6

By Jeff Stander

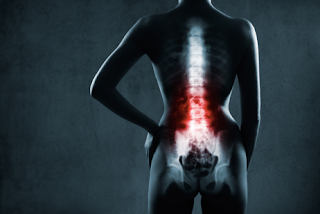

John Jones filed a claim alleging that he injured his back at work. California Constitution, Article XIV, Section 4, expressly empowered the Legislature to devise a system to compensate industrially injured workers so as to achieve substantial justice inexpensively, expeditiously and without encumbrance of any character. The Legislature proceeded to enact Labor Code Section 3600 to express the conditions of compensation for employer liability, Labor Code Sections 4650 and 4656 to define entitlement to Temporary Disability, Labor Code Sections 4658 – 4662, governing entitlement to Permanent Disability, Labor Code Sections 4663 and 4664 pertaining to apportionment of Permanent Disability and Labor Code Sections 4700 – 4706.5 regarding death benefits. The common denominator underlying this entire scheme which determines whether Mr. Jones is entitled to workers’ compensation benefits, and if so, the extent thereof, is expert medical evidence.

The purpose of this article is to examine the necessity and composition of a medical report, the requirement that the medical opinion be based on substantial evidence, the assessment of whether a medical report constitutes substantial evidence, the discovery required to sustain the substantial evidence standard and the application of this standard to various recurring issues in the practice of workers’ compensation.

THE MEDICAL REPORT

Any physician, whether he/she be a Treating Physician, Qualified Medical Evaluator or Agreed Medical Examiner, is required to set forth findings based on the examination and review of records in a report. CCR Section 10606(a) favors the production of medical evidence in the form of written reports. In fact, direct examination of a physician in Court is precluded, absent a showing of good cause. Labor Code Section 4055 mandates that any physician who conducts an exam or is present at the time of the evaluation may be required to issue a report regarding the results thereof. In virtually all cases, medical evidence is necessary to provide the Court with expertise on the various issues. (Twentieth Century Fox Film Corp. v WCAB (Conway) (1983) 48 CCC 275) Given the essential nature of the medical report, the opinions expressed therein, if uncontradicted, will be binding on the subject-matter before the Court. (LeVesque v WCAB (1970) 35 CCC 16)

CCR Section 10606 provides the framework for the required content of medical reports. Any report must express the date of the exam, history of injury, the patient’s alleged complaints, a listing of all information received in preparation of the report or relied upon for the formulation of the physician’s opinion, the medical history, the findings on examination, the diagnosis, the opinion regarding the nature, extent and duration of disability, the cause of same, the opinion regarding MMI status, the existence of any permanent disability, whether the permanent disability is apportioned to non-industrial causes, the signature of the physician and, most importantly, the reasons for the decision.

Because the physician’s report is viewed from the perspective that the contents would be those matters which he/she would testify if called as a witness at the time of Trial, Labor Code Section 4628 specifies that only the physician who signs the report can examine the employee, and that the practitioner must obtain a complete history, review and summarize all medical records, formulate conclusions and specify the date and location of the examination.

Once a medical report has been generated, it will be filed and served in accordance with CCR Section 10608. The report must be served on all parties and all physician lien claimants within 10 days from the date of the request or within 10 days from the date of the filing of a Declaration of Readiness to Proceed. Medical reports and other evidentiary items must be served on all adverse parties no later than the Mandatory Settlement Conference, pursuant to CCR Section 10601. However, the filing of a medical report does not constitute an offer of same into the evidentiary record. Any such report must be formally offered in evidence at the time of Trial, pursuant to CCR Section 10600.

Thus, at the outset, the sufficiency of any medical report must be determined by whether it satisfies the minimum requirements contained in CCR Section 10606 and whether all obligations of the physician set forth in Labor Code Section 4628 were discharged. The failure to satisfy these criteria will render the medical report to be without value.

SUBSTANTIAL EVIDENCE STANDARD

Assuming that the minimum requirements of Labor Code Section 4628 and CCR Section 10606 are satisfied, how can the Court determine whether to accept the opinions of the physician regarding causation, Temporary Disability, Permanent Disability and Apportionment as set forth in the medical report? Labor Code Section 5952(d) provides that the decision of the Trial Court can be reversed by the District Court of Appeal where the “order, decision or award is not supported by substantial evidence.” Of course, that statute fails to define “substantial evidence.” This subjective term evokes similarities with the difficulty encountered by the United States Supreme Court in defining obscenity. Justice Potter Stewart, in Jacobellis v Ohio (1964) 378 US 184, simply stated “I know it when I see it.”

Throughout the years, the Appellate Courts in this state have made numerous attempts to define this vague standard in order that it could be a foundation to guide the Trial Courts in determining whether the reports of physicians satisfied this requirement. The Supreme Court, in Hegglin v WCAB (1971) 36 CCC 93, proclaimed that not all expert medical opinion constituted substantial evidence upon which the Court could predicate its decision. In Liberty Mutual Ins. Co. v WCAB (Serafin) (1948) 13 CCC 267 proclaimed that medical evidence is to be given the weight to which it appears in each case to justly deserve. The Supreme Court, in U.S. Auto Stores v WCAB (Brennan) (1971) 36 CCC 173, mentioned that the considered opinion of a single physician, though inconsistent with the opinions of other doctors, may constitute substantial evidence. In Power v WCAB (1986) 51 CCC 114, the Court held that the report of an AME would be deemed to constitute substantial evidence despite the fact that it contradicted the conclusions contained in the reports of other physicians. A further attempt was made to concretely encapsulate the concept of substantial evidence was made by the Supreme Court inJudson Steel Corp. v WCAB (Maese) (1978) 43 CCC 1205, where it mentioned that even if the findings of the WCAB are supported by inferences that may be fairly drawn from evidence that is susceptible to opposing inferences, the Appellate Court won’t disturb the findings as long as the evidence is substantial. Again, without defining this elusive concept, the Court, in Vela v WCAB(1971) 36 CCC 807, stated that expert medical opinion does not always constitute substantial evidence upon which the WCAB could predicate its decision.

The most comprehensive attempt to convey the meaning of substantial evidence was expressed by the Supreme Court in Braewood Convalescent Hospital v WCAB (Bolton) (1983) 48 CCC 566. Substantial evidence meant evidence “which if true has probative force on the issues. It is more than a mere scintilla and means such relevant evidence as a reasonable mind might accept as adequate to support a conclusion. It must be reasonable in nature, credible and of solid value.”

During the past 34 years, the concept of substantial evidence has been made more objective and placed in sharper contrast. Several specific principles have been enunciated which clarify when a physician’s opinion is, or is not, substantial evidence. These principles will be examined, along with the means of utilizing discovery to elevate the physician’s conclusion to the level of substantial evidence.

=================================================================================

R. Jeffrey Stander is Of Counsel to Stander Reubens Thomas Kinsey. Prior to joining the firm in 1982, he was associated with law firms exclusively handling workers' compensation and general civil matters, and acting as in-house counsel for Western Employers' Insurance Company. Mr. Stander is a Certified Specialist in Workers' Compensation law, a member of the Assessment Committee of the Lawyers’ Assistance Program for the State Bar of California, and has been an instructor for the Insurance Educational Association. He received his Bachelor’s degree from the University of Southern California and his Juris Doctor degree from the University of San Fernando Valley College of Law. (www.srtklaw.com/attorneys)

Nconsmagtheika Mark Hogan link

ReplyDeletepliftiltizets