The Conundrum of Medical Inflation

By Judge David Langham

There is so much happening in workers’ compensation right now. It seems that every week brings revelations and discussion. There are a myriad of changes occurring across the country, and I was honored last week to discuss some of them with the Mississippi Workers’ Compensation Education Association gathering in Biloxi.

One foundational element to me is medicine and economics. For decades, the rate of inflation for medical services in the United States has risen more rapidly than inflation in the general economy. As a result, medicine is consuming more and more of our personal, state, and national budgets. That care is being delivered is laudable. But, those cost increases are creating pressures. The ratios used to demonstrate indemnity (lost wage) benefits as the predominant workers’ compensation expense, but medical costs have overtaken indemnity, and continue to grow.

The pressure is illustrated by the effect Medicaid has on state budgets. In 1996, approximately 20% of state budgets went to Medicaid according to Internal Medicine News. In 2017, that figure now approaches 30%. Over the last twenty years, the costs of goods and services and wages have risen in the marketplace. Inflation, based on the consumer price index (CPI), measures that. As prices (sales/service) and wages (income) increase, so do tax (sales or income) revenues upon which state rely.

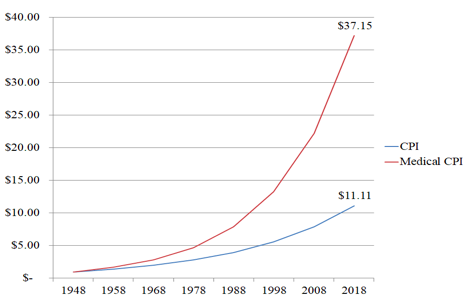

But, those tax revenue changes are based on percentages of the prices or wages of the underlying transactions. Though inflation has increased tax revenues, which has not kept pace with medical inflation. As the market has seen inflation, the rate for medical goods and services has been about “70% faster” than the general market according to the St. Louis Federal Reserve. It notes that since 1948, inflation generally has averaged 3.5% while medical inflation has averaged 5.3%. This is a marked difference.

To illustrate, imagine a family that has only two expenses. Economists find that explaining markets becomes somewhat easier when they are simplified in this manner. In my youth, they asked us to cogitate on an economy making decisions between producing “guns or butter.” But imagine a hypothetical family that is purchasing only lodging and health care. Imagine that these two do not “inflate” at the same rate, but medical inflates at 5.3% and lodging merely at 3.5% (as seen historically over the last 70 years). For the sake of our model, the family is fortunate that its income is subject to regular cost of living increases, based on the CPI and the “general” rate of 3.5%. I say fortunate because some families see little to no income increases.

Thus, the lodging expense over the last seventy years would have increased significantly. One dollar in 1948 would have inflated to just over eleven dollars in 2018 (illustrated below). But the one dollar in medical care in 1948 would have increased to just over thirty-seven dollars. The two categories of spending were equal in 1948, and now one is almost four times the other. As salary and earning likely increased at a rate close to the CPI, the medical care costs explode. This is part of the explanation of the increasing share that medical care takes of the various budgets.

Another factor that bears discussion is the changing face of science. Over the last 70 years, there has been an amazing array of medical “firsts.” According to the New York Times, since 1948, we have seen the first mechanical heart, magnetic resonance, heart-lung bypass, cochlear prosthesis, kidney transplant, pacemaker, liver transplant, portable defibrillator, heart transplant, CT scanner, MRI, synthetic blood, DNA sequencing, the human genome, artificial joints and organs, and more. Those advances required research, recovery from failed attempts, and they are expensive.

Until recently, the American life expectancy kept rising each decade. Survival rates for a multitude of diseases have increased. Science has been a boon, but it has also been expensive. Those medical procedures have made it possible for people to retire and live significant times thereafter. That has strained the retirement system, but it has also increased demand for medical care and services. Diseases that once killed mercilessly have been held at bay, but with expensive medicine. And, as we age, we are likely to encounter more medical challenges. Thus, kept alive by expensive innovations, we remain in the market as consumers of even more expensive innovations.

Long ago, America decided to socialize medical care. Not for everyone, but for some. The enactment of Medicare and Medicaid has increased the population of people seeking care. National Public Radio describes well how medicine evolved and changed in the 1920s. It “became much more effective, and much more expensive.” And that cost was paid by individuals, group health, workers’ compensation, Medicare/Medicaid, the Veterans’ Administration, and more. But the “disconnected payer” has contributed to the spending.

If I am told I need a $1,000 medical test, I may be reluctant to undergo it. But, if I am told that I need only pay my $40.00 co-pay and insurance will pay the rest, I may be less reluctant. In fact, just to be sure, I may go ahead and have two of them. The decision maker (patient) is detached from the financial burden of the decision. If our consumption of other goods such as food or automobiles worked this way, I would eat much more steak and drive a Cadillac. But, with other consumption, we pay the real costs. With food, electronics, housing, and more there is no limitation to a copay or deductible, no government subsidy.

So, a family in 1948 spending 10% of its income on medical care would by today have seen that percentage increase markedly. Income and overall inflation simply does not keep up with medical inflation. This is changing the marketplace. Injured workers seek the best and newest care, while those paying the bill are more interested in the least expensive alternative. New drugs are introduced to market and old drugs reach the limit of their protection, face competition from generic substitutes, and decline in profitability. The payers prefer the generics; the patients seek the “latest and greatest.”

The producers are incentivized to expedite revenue and then seek to patent the next “big thing.” They are developing, producing and distributing new and bigger and better all the time. Not content to convince doctors to deploy their latest and greatest, they bombard us on television, radio, and more. They promise and commit and send us to the doctor demanding their latest improvement.

As a result, states and families are paying larger medical care costs. For states, this is actual payment, but for consumers it is likely disguised as health insurance costs. But, each continues to rise. And, despite these increased costs consensus holds that Americans do not enjoy the most successful medical care.

Critics complain that this is due not to our medicine, but to our payment model. They lament the use of “pay for services” in which doctors, hospitals and more enjoy a benefit from each test or procedure that is performed, even when there is no provable benefit to the patient. Treatment, they contend, is recommended because it benefits the doctor, the hospital, or the facility. They stress that this can be turned around. They advocate that the success of care (outcomes, recovery, return of function), is the appropriate measuring stick. They assert that more money should be paid to those who inspire and produce better outcomes, rather than those who perform the most testing or procedures.

There has been a significant amount of debate about medicine in America. But the promises of socialism have fallen short across the globe. The one truth that is in the numbers is that medical cost in America is increasing significantly and persistently. Medical costs are consuming increasing portions of state, federal, and personal budgets. Socialism has not proven itself an effective model in any scenario, and has utterly failed in non-totalitarian instances. As a free nation of free people, we must strive to understand that.

Our medical model must be revised and revamped. We will have to accept that utopian ideals of everything for everyone with low or no costs for all are untenable. We must build a model that incentivizes positive outcomes, recovery, and restoration of function. The numbers tell us that the path we are on is simply not sustainable, and the brilliant and gifted among us must change our course. It is time.

Comments

Post a Comment